Lubna Irfan, Junior Research Fellow, Aligarh Muslim University

There has been an exciting debate around the nature of the divide between the private and the public spheres in Mughal India. Scholars such as Rosalind O’Hanlon and Ruby Lal have tried to theorize this divide in the context of pre-modern Mughal consciousness and society. They evoke medieval Perso-Islamic political culture to give meaning (with certain exceptions) to the masculine public and the feminine ‘incarcerated’ private sphere.

This divide can further be approached and problematized by exploring the category of ‘service’. This piece attempts to do so by looking at the role of eunuchs in the Mughal empire.

The Eunuchs or Khwajasaras, which is the Persian term for a range of men with removed or non-functional sexual organs, were employed in the Mughal empire as slaves, servants, and administrative officers. They were both slaves and slave owners, and at times they worked as brokers in sustaining the system of slavery.

Their divergent sexuality socially put them in an ambiguous position in the Mughal setup but they undeniably formed an integral part of both worlds: of the Mughal harem as well as Mughal public sphere.

The private and the public

With recent studies highlighting the porous boundary between the private and the public as a chief characteristic of the early modern period, eunuchs’ role in maintaining as well as transgressing these boundaries become highly interesting to explore. The most important service they performed was related to their critical role in the exchange of information.

The eunuchs were the most important source for the knowledge of the harem to the outside world and vice versa. Abul Fazl, the author of Akbarnama, which is a major primary source of information on Mughal India, informs us that all the intrigues and gossips travelled through the means of this servile class. Francois Bernier, the French traveller who visited Mughal court of Aurangzeb in the seventeenth century, gives details of the organization and arrangement of the Mughal harem based upon information he garnered from the eunuchs.

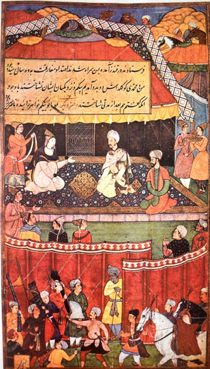

Figure 1: Babur meeting a princess, work of Mansur, Baburnama, AD 1598, National Museum, New Delhi.

In the frame, near the tent entrance apart from two men, can be seen Khwajasaras in service of the princess.

They occupied the space of the harem and the bazaar and in so doing became an important link between the two. It also needs to be pointed out that the information that was circulated by eunuchs was not only of popular nature but also confidential. When Aurangzeb had fallen ill around 1662, it was only through the trusted eunuchs of Roshan Ara, the sister of Aurangzeb and Muazzam, the son of Aurangzeb, that the information was exchanged about the life of the Emperor.

Many contemporary observers who occupied the bazaar space have criticized eunuchs for being gossip mongers. They have been highly ridiculed for ‘listening amongst kings, princes, queens and princesses’, as Manucci reported. This form of anxiety associated with them suggests that their role in obtaining and then disseminating information of various types affected the political, social, and cultural dynamics of the Mughal empire.

Foregrounding this largely unexplored aspect of Mughal history and, in that the process, exploring the under-studied aspect of services provided by the ‘third gender’ seems important to develop a complete picture not only of the Mughal private life but also its public, political, and cultural dimensions.

The administrative and political role played by the eunuchs has been underplayed or ignored in most of the writings on Mughal state. For example, K.S. Lal, Gavin Hambly and others, while acknowledging the multifaceted role played by the eunuchs, exclusively highlight their involvement in the harem. It is because of this narrow historical characterisation that today the only space associated with the image of a Medieval Indian khwajasara is that of the Mughal harem.

A perusal of the contemporary sources reflects that eunuchs used to perform administrative, religious, and managerial duties. Sometimes, the nature of the duty was similar to the ones usually undertaken by important nobles.

For example, Abdullah Khan, an amir (noble) of Jahangir’s reign, sent his Khwajasara Wafadar (the Loyal Eunuch) to govern the province of Gujarat, which was a location of great strategic significance on the western coast of the subcontinent. Eunuchs, on certain occasions, took a stand in opposition to princes of royal blood; Itibar Khan Khwajasara who was one of the closest confidants of Jahangir, defended the city of Agra against Shah Jahan, the future Mughal emperor and the rebel prince of Jahangir’s period. Another Itibar Khan, a confidante-servant of Babur, was made the governor of Delhi during the reign of Akbar. Dara Shikoh also appointed a khwajsara as the governor of the fortress of Attock by the river Indus. Khwajasara Khwaja Agah was given the charge of faujdarship (governorship) of Agra. These numerous examples clearly show that eunuchs’ participation in the political power play and administrative duties of the empire was contemporaneously acknowledged.

The historians’ gaze has somewhat muzzled this past.

Figure 1: Khwajasaras can be seen peeping from the door in the upper left portion of the painting.

A 17th century copy of an original Akbarnama painting depicting the scene of Adham Khan’s punishment. Courtesy Geeti Sen, Paintings from Akbarnama

Inside the harem

True to their positioning in the seams of empire, eunuchs’ role in the harem was also of managerial and administrative nature. They were the in-charge of the security of the place. They guarded the harem against the entry of unwanted men and objects which had sexual connotations and could be used by women for sexual pleasure, such as cucumber, nutmegs etc. A proper hierarchical system was in place at the royal harem where there were eunuch in-charges called nazirs who were mainly supervisors. They were assisted by other subordinate khwajasaras.

In the process of protecting the harem, the eunuchs, at times, misbehaved with the women inmates but at other were at the receiving end of the harsh treatment as well. An important example of the latter is the dismissal of the in-charge of the royal harem by Aurangzeb when it was discovered that two young men had entered the harem. This breach of security was reportedly committed in the knowledge of Raushanara Begum, but the burden of the mistake was borne by the eunuch.

Harem women could also seek sexual services from the eunuchs. There are a few indirect evidences to this where a contemporary observer, Manucci, writes how women of the harem sometimes took favours from the eunuchs who used their tongues and hands in the most ‘licentious’ manner. Further, there is at least one reference to a eunuch having an affair with a woman during Aurangzeb’s reign. In this incident, the eunuch was murdered for the apparent sin he had committed.

Political rivalries also engulfed them. Khwaja Hilali of Akbar’s court was made to give up on his beloved house because another noble got a liking to it. Aitmad Khan, another eunuch holding considerable power under Akbar, was stabbed by a common soldier because of his harsh attitude.

Gender and persecution

This kind of persecution of eunuchs can be taken as a representative example of many other reported incidents of violence of various forms against the group of ‘third gender’. This violence seems to be rooted in the essential non-man nature of eunuchs, which must have threatened a largely patriarchal Mughal world. The narratives of the contemporary records reveal male anxiety where eunuchs are presented as metaphors of absence, as representative of a valance, both physical and psychological. This sense of inferiority might have been true in some cases but truly was not the only representative reality of the eunuchs’ lives.

There are two reported incidents where eunuchs gave voice to such pain of absence. One was the mention where Aitbar Khan cursed his parents of depriving him the ‘man’s greatest pleasure’ and the other was of Daulat eunuch who, when lost his nose and ears, lamented of being made into a eunuch twice over. In contrast to these examples there are abundant references where eunuchs faithfully served their masters and provided services to the Mughal state, without any sense of inferiority arising due to their ‘gender’. The eunuch of Murad Baksh, the brother of Aurangzeb, even gave up his life for him.

The contemporary informers have been harsh with the eunuchs in calling them animals and baboons, greedy for riches and doing licentious deeds.

The historical lens of service allows to go beyond such representations and at the same time contextualise them in the larger politics of bodily practices, political power, gendered essentialisations, and everyday sinews of control and authority extending between the court, bazaar, and harem.

Seen in this light, it makes sense to see why some other representations of eunuchs complained of them exercising more power than they deserved to wield. This nature of reported information can be contrasted with the fact that the royals kept eunuchs as close confidants and gave them titles signifying they were trustworthy, loyal, and reliable. The titles like Itibar and Aitmad, both meaning trustworthy and faithful, have been given time and again to important eunuchs from Akbar to Shah Jahan’s reign, suggesting their sincerity to their superiors who were in most cases males.

The fact of social exclusion, however, cannot be dismissed. Undue persecution of eunuchs is also observable in the sources. The apparent cases of persecution can be supplemented with more subtle, everyday persecution faced by eunuchs.

Interestingly, eunuchs seem to have not formed an exclusive identity based on their gender. Instead there are references where they themselves oppressed fellow eunuchs, as was the case in the harem. One instance where they formed a group and addressed their demands to the emperor was in the case mentioned above where after the eunuch who had an affair with a woman was murdered, the entire harem of the emperor including the eunuchs and the ladies rose up in rage to demand punishment for the murderer.

Service providers

While gender and chastisement helps to explore this little-known history of the eunuchs, it is equally promising to see them through the cast of service providers, the service which ranged across the spectrum of the public and private spaces of the Mughal empire. Their service ranged from being close loyal personal servants to that of being the loyal governors. The most important fact is that the idea of loyalty and patronage was ingrained in the nature of the services evoked from eunuchs. The nomenclature and titles which imposed on them the idea of trustworthiness also asserts the primacy of providing personal services to the royal and noble personages.

Most of the royalty and nobility, including women, employed some eunuchs as private service providers. Hence the domestic and personal aspect of a eunuch’s services seems to be the principal characteristic of their lives and services. When the idioms of politics were themselves personalised, the extent of the service, by default, stretched from the court to the harem.

Having stated the primacy of the domestic nature of service performed by the eunuchs, it needs to be asserted that as a service class they were providers of all four kinds of services mentioned by Abul Fazl. The four categories of servants of the empire mentioned by Abul Fazl are: nobles of the state; assistance providing functionaries of the state; companions of the emperor; and personal servants who waited upon the emperor and his family. There are examples given above which make eunuchs important part of all these categories. In fact, they were the only group of service providers who had this distinctive feature of covering such a range.

This further makes them an integral part of both the private and the public spheres and in the process their presence questions the public-private divide itself. Looking at eunuchs from beyond the lens of gender and through that of service brings forth the fact that the public-private divide of the Mughal empire was increasingly challenged not only by occasional assertion of authority by women, as argued by Ruby Lal, but also by regular presence and movement of the eunuchs across this porous divide.

By hinging upon the service provider identity of eunuchs, we can bring forth aspects of Mughal world which have been missed out because of limiting the history of eunuchs mainly to the harem. The ‘domestic’ services provided by the eunuchs were not limited to the harem, and their services formed an important part of all the categories of the Mughal services.

This is a really informative piece. Could you please provide the citations for the first image you have used? Thank you so much!

LikeLiked by 1 person