On 21st August 1818 Ramonee, a thirty-year-old woman from Patna, appeared before the Supreme Court at Fort William, Calcutta. Ramoone, who worked mostly as an ayah (nanny, lady’s maid), was brought as one of the witnesses in a case brought forth by her employer Major Cunliffe (a military captain stationed in Cawnpore in north India) accusing his wife Louisa for adultery. A charge of adultery directed against wives, as it was also prevalent in England at that point in time, enabled husbands to sue for damages against the accused adulterer. This was followed by proceedings in the ecclesiastical side of the court for a separation from bed and board (similar to legal separation). A full divorce (which itself was extremely rare and privilege of the rich and influential) required a private act of the British parliament and usually cost a fortune.

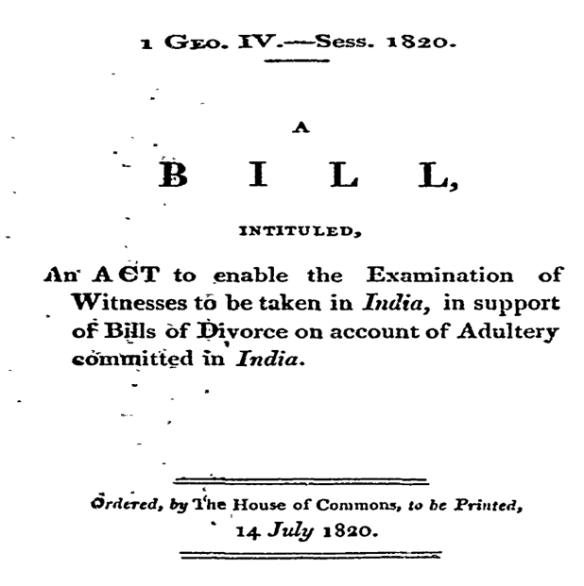

There was another problem for the British residents in India even if they wished to or were capable of taking this route. The witnesses necessary to establish the charge (often servants, other household members, friends, acquaintances and colleagues) could not technically travel to England in each and every case to submit before the parliament. A particular change in regulation (in 1820) where the Supreme Courts of Calcutta, Madras and Bombay were permitted to summon witnesses and collect evidences to substantiate these allegations made by the husbands (directed by a warrant issued by the British Parliament) came into force that made divorces possible in India.

The recorded evidence and the details of the trial were then forwarded to the parliament for a dissolution of the marriage. The details of this particular case and Ramonee’s testimony, therefore, became available because of this change in regulation when Major Cunliffe applied for a full divorce in 1823.

Here I am less concerned with the new anxieties around adultery and the practices of divorcing (interesting in itself) but the possibility this legal procedure (i.e. divorce trials) opened. To us historians it gives a unique chance to hear servants as they were summoned by the court to testify in support of their masters’ claim that their mistresses have committed adultery. I have been able to collect around thirty trials spanning a period of 40 years (the early 1820s to early 1860s) held at the Supreme Courts of Calcutta, Bombay, Madras and Ceylon.

The testimonies of the servants, numerous as they are, do not in any way directly reveal their personal biographies and work experiences but by the nature of questioning are narratively framed towards establishing the guilt of their mistresses. An attempt to understand the nature of domestic service and domestic relationships in the nineteenth century British households through an examination of divorce trial does not intuitively appear as a productive research strategy. So why divorce trials?

There are a few immediate reasons for this. The nature master and servant relationship as described in the literature (both contemporary and historical) is often an interrogation of perspectives which can broadly be described as employer’s. This literature depicts how the European household in India was marked by a vast retinue of servants, showing occupational segregation and hierarchical organisation. There is a substantial exploration of the anxieties of the master with respect to their servants in which their dependence and proximity towards them are shot through racial, class and colonial tensions. Such perspectives, though crucial in understanding the nature of master/servant relationship, is heavily loaded in favour of interrogating the experiences and notions of the employers. The nature of material through which these histories are written offer little to examine any other perspective but the employer’s.

My initial research on ayahs heavily relied on this material but I was also struck by how little I could tell about women who worked as ayahs in European households. There was a lot of material (textual, visual, and literary) to describe how the employers celebrated and feared ayahs but I could hardly assess if the so-called ayahs shared those views or could have some other take on this relationship. Were they sharing the sense of intimacy with the memsahibs and infants and were they also anxious about the violation of caste and racial boundaries? In an attempt to probe these issues further I took the advice of good old social historians and particularly what came to be described as micro historians: who read the judicial archives carefully and creatively to write the history of the marginal. Here I am thinking of the classic works of Carlo Ginzburg and Natalie Zemon Davis. Again, the disproportionate presence of servants in a set of published trials of divorce drew my attention towards it. Like most other cases in the archives in which servants appear, they are not the protagonists but their presence in courts as witnesses offered some new possibilities.

Coming back to the story of Ramonee: she briefly worked as an ayah in the household of Robert Cunliffe and Louisa. In early 1817, Louisa Cunliffe went to Calcutta by boat with two of her older children who were being sent to England. This, as we know, was a common practice of children leaving their parents based in India to attend school in England. On her way back to Cawnpore, Louisa Cunliffe was accompanied by one Mr and Mrs Loftus with their young infant child. Loftus was taking charge as an army captain in Cawnpore and it appears that Louisa Cunliffe was an older acquaintance or even a friend. The arrival of the Loftus family with an infant required an ayah and Ramonee was hired through a reference (another ayah), working in Cawnpore. The families lived together in the same bungalow which allowed Ramoonee to often notice the movement of Mr Loftus towards Louisa Cunliffe’s bedroom late in the night.

Her evidence in the ecclesiastical court in 1818 was therefore crucial in establishing the affair between Mr Loftus and Louisa Cunliffe. When the case came up in 1823 for a divorce (which was available for British subjects from 1820), the supreme court of Calcutta ordered the witnesses to be re-examined. It was quite evident that Ramonee’s account was the most pivotal in establishing the details of the case and therefore she was summoned to appear in court. But Ramonee in the meantime had left the employment of Cunliffe and could not be immediately traced. A search for Ramonee at the behest of the court and Mr Cunliffe gives us some details about her life from 1818 (when she first appeared in court) until 1823 (when she was expected to reappear).

In this particular case, the fact that Ramonee went missing, led to a search which allows us to reconstruct some biographical details about her. This would not have been possible if she was immediately found. This search was conducted through servants of the household who knew Ramonee from work. A couple of them had even accompanied her when she came to Calcutta at an earlier stage of the case. One of the servants, who accompanied Ramonee on a boat journey from Cawnpore to Calcutta, mentioned in the court that Ramonee insisted on making a stopover in Patna as she wanted to visit her ‘family and relations’. After making this particular halt in Patna, Ramonee along with the fellow servant visited the house of Imam khanun, described by him as a Muslim woman of repute. Ramonee referred Khanun’s household as her home. This might be a sisterhood household, where single women possibly outcastes or widows could find refuge.

Ramonee after having stayed there for a couple of days proceeded to Calcutta. In Calcutta, Ramonee along with her fellow servant stayed in the house of Mr Hunter (an acquaintance of Mr Cunliffe) and later took up an employment there. After the initial trial, the other servant left for Cawnpore but Ramonee stayed on in her new job. Working with these leads, another servant was sent to find her in Patna and he again visited the household of Imam khanun. She mentioned that Ramonee had left her job in Calcutta and had returned to Patna around 1819-1820. This was the time of a raging cholera epidemic and Ramonee having fallen ill moved out of the house with another female inmate of the house (a Hindustani woman) and could not be traced any further.

Let me briefly recap this story. Ramonee, a thirty-year-old woman from Patna, working through references (she was employed for Cunliffe in Cawnpore through reference and also her job in Calcutta was based on her reference from her former employer) found work as an ayah in the household of Europeans. Ramonee moved in the region from Cawnpore to Calcutta frequently going back to what she described as her ‘home’ in Patna, that is, the household of Imam khanun. We know little about her social and marital background. Was she ever married or was widowed? It seems she was a Muslim or a lower caste woman. Again we know very little about the circular migration of single women like Ramonee in early nineteenth century eastern and northern India. The magisterial survey of Buchanan-Hamilton covering this region in the early part the century offers little to explain their presence. Did the setting up of European households in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century with a demand for household servants based on gender, caste and religion create a market for wages for women like Ramonee? Again how do we situate the household of Ramonee: a sisterhood of single women which included lower castes, Muslims and widows?

It seems that ayahs like Ramonee and others ayahs who appeared in other cases rarely had a long-term engagement with a particular household and their working lives were marked by a series of short-term employments and even periods of a break from work before they would take up future employment. There were other instances of kin members (often daughters) substituting in times of absence or transfer of the employer. It does not seem that ayah work was a lifecycle employment as women would work as ayahs through their working careers mostly in several short-term engagements. Again it appears that ayahs working in European households sought employment in another European household (through references and the developing chit system) and there was little movement of servants between European and non-European homes. The nature of the employment seemed to be highly specialised as ayahs were hired either to take care of infants and in that case termed as child’s ayah or to attend to the mistress and then referred as lady’s ayah. This specialised nature of work also explained the shorter stints of employment. Some ayahs were specifically hired during childbirth and would often be discharged after a few months of delivery, or ayahs taking care of smaller children would find themselves out of work when the kids were sent to England for school which usually happened when they turned five.

This specialised nature of work also allowed for a particular personalization of authority when ayahs attending the lady and the children were seen attached to the mistress and would move with her in instances of the mistress leaving the household due to marital discord. The male servants, especially bearers, were seen as under the master’s command and seemed to have been employed for longer periods in comparison to ayahs. The question of intimacy becomes relevant in this context. Did these short-term engagements allow a possibility to develop close and intimate ties? For instance, did Ramonee who took care of the infant in Cawnpore felt attached to the child? Was her leaving the job marked by emotional trauma and pain? It is difficult to offer a conclusive answer but at least we are alerted to the limits of the representation which celebrate deep loyalty, attachment and fondness between ayahs, mistresses and children.

I have tried to suggest the limits of the material on which the histories of domestic servants and service relationship are usually constructed and the possibility the divorce trial can offer. This material, however, presents its own set of challenges. It is necessarily directed towards a particular kind of interrogation. Individuals appear briefly and within the limits of this inquiry. Yet the possibility of reconstructing the relationships existing within the household and also biographies of some individuals working as servants, as we have seen in the case of Ramonee, appears to be probable.

By Nitin Varma

thanks

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting to know that British Parliament granted Divorce in 1820s!

Further to know that there were Supreme Courts (? Judicial Hierarchy) in Calcutta Bombay Madras and also at Ceylone – Even then they were extremely inefficient – a witness required to be ‘reexamined’ after five years!

Ramonee name does not give a clue for her caste / religion background!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the comment. It seems that this particular case was crucial in making divorces possible for British subjects in India. The reason for these time lags was also due to the fact that some of these cases of “adultery and divorce” went through different legal stages (seeking damages from the accussed adulterer, legal separation from the wife and in some cases–full divorce). There are many details which one would like to know (for instance, about Ramoone’s case and religion; and I am very much invested in further developing this story (through detailed reading of the period from other sources and also some “informed speculation” as a methodology). I hope to reflect more on this in my next post.

LikeLike